- Home

- Bill Gammage

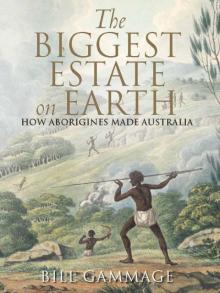

The Biggest Estate on Earth

The Biggest Estate on Earth Read online

The

BIGGEST

ESTATE

on EARTH

Other books by Bill Gammage

The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War

An Australian in World War I

Narrandera Shire

The Sky Travellers: Journeys in New Guinea 1938–1939

Co-authored:

The Story of Gallipoli

Co-edited:

Australians 1938

Crown or Country: The Traditions of Australian Republicanism

Hail and Farewell: Letters from Two Brothers Killed in France in 1916

Six Bob a Day Tourist

The

BIGGEST

ESTATE

on EARTH

HOW ABORIGINES MADE AUSTRALIA

BILL GAMMAGE

First published in 2011

Copyright © Bill Gammage 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 748 3

Internal design by Nada Backovic

Set in 11/15.5 pt Caslon Classico Regular by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Printed in China at Everbest Printing Co.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the people of 1788,

whose land care is unmatched,

and who showed what it is to be Australian

Fire, grass, kangaroos, and human inhabitants, seem all dependent on each other for existence in Australia; for any one of these being wanting, the others could no longer continue. Fire is necessary to burn the grass, and form those open forests . . . But for this simple process, the Australian woods had probably continued as thick a jungle as those

of New Zealand or America . . .

THOMAS MITCHELL, SYDNEY, JANUARY 1847

. . . observing that the grass had been burnt on portions of the flats the Blacks said that the rain that was coming on would make the young grass spring up and that would bring

down the kangaroos and the Blacks would spear them from the scrub.

OSWALD BRIERLY, EVANS BAY, CAPE YORK, 1 DECEMBER 1849

CONTENTS

Illustrations

Thanks

Sources

Abbreviations

Definitions

Foreword by Henry Reynolds

Australia in 1788

Introduction: The Australian estate

1. Curious landscapes

2. Canvas of a continent

Why was Aboriginal land management possible?

3. The nature of Australia

4. Heaven on earth

5. Country

How was land managed?

6. The closest ally

7. Associations

8. Templates

9. A capital tour

10. Farms without fences

Invasion

11. Becoming Australian

Appendix 1: Science, history and landscape

Appendix 2: Current botanical names for plants named with capitals in the text

Notes

Bibliography

ILLUSTRATIONS

All illustrations are in chapter 2.

Pictures 1–4: Light

1. Swamp Gum

2. Yellow and Apple Box

3. White Gum

4. Blakely’s Red Gum

Pictures 5–12: Fire

5. Snow Gum

6. Eucalypts and acacias

7. Ribbon Gum

8. River Red Gum

9. Snappy Gum

10–11. Kangaroo Grass

12. Eaglemont 1889

Pictures 13–22: Broad-scale fire

13. Endeavour River 1770

14–15. Esk River 1809 and 2008

16. Mills’ Plains c1832–4

17. Onkaparinga 1838

18. Adelaide c1840

19. Ginninginderry c1832

20. Near Melbourne 1847?

21–2. Mt Eccles 1858 and 2007

Pictures 23–30: Arid-zone fire

23–4. Spencer’s Kantju 1894 and 2005

25–6. Spencer’s Uluru 1894 and 2005

27–8. Mountford’s Uluru 1938 and 2005

29–30. Great Sandy Desert 1953 and 2005

Pictures 31–37: 1788 fire patterns—edges

31. Constitution Hill c1821

32. Lively’s Bog 1998

33. Wannon Valley 1858

34. Wingecarribee River c1821

35. Swan River 1827

36. Mt Lindesay c1829

37. Milkshake Hills 2002

Pictures 38–41: 1788 fire patterns—patches and mosaics

38. Snowy Bluff 1864

39. Deadman’s Bay c2001

40. Bunya Mountains 2003

41. Near Mudgeegonga 1963

Pictures 42–52: 1788 fire patterns—templates

42. Wineglass Bay c2001

43. Branxholm 1853

44–5. Cape York 1891

46–7. Gatcomb 1949 and 1984

48. Gatcomb 2002

49. Kadina 1874

50. Bundaleer 1877–8

51–2. Lake George 1821 and 2009

Pictures 53–58: Templates in use

53. Hunting kangaroos c1820

54. Using fire c1820

55. Spearing fish c1820

56. Barwon Valley 1847

57. King George Sound 1832

58. Somerset 1872

Picture 59: A European mosaic

59. Kangaroo Island 1983

THANKS

This book is about achievements of people I never knew. Far too late, I thank them.

Before everyone else I thank my wife Jan. She has always helped my work, but for this book more than any other she gave up much, with extraordinary patience and good humour over many years. She made the book possible.

I next thank three friends, clear-eyed readers: Henry Nix, Henry Reynolds and Denis Tracey, for polishing a draft and for help along the way. I thank Henry Reynolds especially, for years of encouragement, and for his generous foreword.

I thank the Humanities Research Centre at the ANU for hosting my research, and an ARC Fellowship for generously supporting part of it. I thank Pip Deveson, Leena Messina, Mike Powell, Jill Waterhouse and especially Gurol Baba for help with images, and I thank the staff of the archives and libraries listed in the Abbreviations, especially my friends at the National Library of Australia. I thank Elizabeth Weiss at Allen & Unwin for her promptness, courtesy and efficiency.

The following list makes clear how impossible it is to thank as they deserve the many other people who helped me:

ACT: Bryant Allen, Don Baker, John Banks, Tim Bonyhady, Ian Brooker, Phil Cheney, Bill Clarke, Bob Cooper, Jan Cooper, Helen Diga

n, Mary Eagle, Brian Egloff, Barney Foran, Kevin Frawley, Alison French, Ian Gammage, Jake Gillen, Jack Golson, Janda Gooding, Peter Greenham, Chris Gregory, Niel Gunson, Stuart Hay, Luise Hercus, Robin Hide, Geoff Hope, Iain McCalman, Neal McCracken, Kim McKenzie, George Main, Sally May, John Merritt, Howard Morphy, John Mulvaney, Daphne Nash, Hank and Jan Nelson, Jim Noble, Penny Olsen, David Paterson, Nic Peterson, Tony Vale, Gerry Ward, Elizabeth Williams.

France: Laurent Doussot.

NSW: John Blay, Denis Byrne, Janet and Jim Fingleton, Nic Gellie, David Goldney, Helen Harrison, David Horton, Christine Jones, Ian Lunt, John McPhee, Chris Moon, Eric Rolls and Elaine van Kempen, Yuji and Hiroko Satake, Rob Sellick, Stan Walton, Peter and Bunty Wright.

NT: Dave Bowman, Jim Cameron, David Carment, Stuart Duncan, Ted Egan, Margaret Friedl, Punch and Marilyn Hall, Dick Kimber, Chris Materne, Julia Munster and Sam Spiropoulis, Vern O’Brien, Tom Vigilante, James Warden, Samantha Wells.

NZ: Ian Campbell.

Queensland: John Bradley, Athol Chase, Mac Core, Arch Cruttenden, Russell Fairfax, Rod Fensham, Bill Kitson, Kate Lovett (Steve Parish Publishing), Yuriko Nagata and Terry Martin, Melissa Nursey-Bray, Anna Shnukal, Brian and Jenny Wright.

SA: Carmel and Eric Bogle, Philip Clarke, Rob Foster, Tom Gara, Diana Honey, Rob Linn, Leith MacGillivray, John and Sue McEntee, Jean and Ron Nunn, Bernie O’Neil, Mick Sincock, Peter Sutton.

Tasmania: Jayne Balmer, Mick Brown, Graeme Calder, Sib Corbett, Fred Duncan, Louise Gilfedder, Andrew Gregg, David Hansen, Margaret Harman, Bill Jackson, Jamie Kirkpatrick, Greg Lehman, Jon Marsden-Smedley, Bruce McIntosh, Bill Mollison, Mike Pemberton, Edwina and Mike Powell, Mitchell Rolls, Lindy Scripps, Bill Tewson, Ivor and Sheila Thomas.

Victoria: Corinne Clark, Peter Coutts, Julia Cusack, Beth Gott, Jeanette Hoorn, Lynne Muir, Mathew Phelan, Judy Scurfield, Frances Thiele, Ian Thomas.

WA: Geoff Bolton, Jack Bradshaw, Neil Burrows, Peter Gifford, Ian Rowley, George Seddon, Tom Stannage, Roger Underwood, Dave Ward.

SOURCES

Few sources here come directly from Aboriginal people. Over the years Aboriginal friends and acquaintances in Narrandera, Alice Springs, the Coorong and northern Tasmania have taught me, but this book discusses all Australia, and I had neither the time nor the presumption to interrogate people over so great an area on matters they value so centrally. Instead there are three main source categories:

• writing and art depicting land before Europeans changed it

• anthropological and ecological accounts of Aboriginal societies today, especially in the Centre and north

• what plants tell of their fire history and habitats.

I have tried to exclude sources reflecting such natural determinants as soil or salt rather than human impact. No doubt I have not always succeeded. To compensate for this, and to defuse a charge deniers of Aboriginal impact make—that there is no evidence for it—I have accumulated a wide range of sources. They come from across Australia—not from every corner, but from more than enough corners to join the dots, for no people would apply such detailed skill and knowledge for so long to most parts, yet not manage the rest, or not know how. I hope the sheer volume and detail of the evidence might support the book’s central argument: that the 1788 landscape was made, that so many records over so great an area cannot all be wrong.

They are a fraction of what exists. Much lies unread or unnoted in the historical record which might answer important questions about Aboriginal land management. At least some answers are lost, but I believe more is possible than this book offers. It is only a start. It merely offers clues on what to look for on the ground and in the records, so that one day Australians might see more clearly the great story of their country.

ABBREVIATIONS

1. Institutions

AGSA Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

ANU Australian National University, Canberra

AOT Archives Office of Tasmania, Hobart

DENR Dept of Environment & Natural Resources, Adelaide

ERM Lands Museum, Dept of Environment & Resource Management, Brisbane

FPB Forest Practices Board, Hobart

FT Forestry Tasmania, Hobart

JOL John Oxley Library, SLQ, Brisbane

LPE Place Names Unit, Dept Land, Planning and Environment, Darwin

LTO Lands Titles Office, Adelaide

ML Mitchell Library, SLNSW, Sydney

MSA Mortlock Library, SLSA, Adelaide

MV Museum Victoria, Melbourne

NAA National Archives of Australia, Canberra

NGA National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

NLA National Library of Australia, Canberra

NPWS National Parks and Wildlife Service

OHU Oral History Unit, NLA

PALM Planning and Land Management, Perth

PWS Parks and Wildlife Service

QSA Queensland State Archives, Brisbane

SAM South Australian Museum, Adelaide

SCMC Supreme Court, Sydney (Miscellaneous Correspondence)

SL State Library

SR State Records

TMAG Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart

UPGS United Photo and Graphic Services, Blackburn, Victoria

VPRS Victorian Public Records Service, Melbourne

WCAA The Wesfarmers Collection of Australian Art, Perth

2. Sources

AAAS Australian Association for the Advancement of Science

ADB Australian Dictionary of Biography

BG Bill Gammage

BPP British Parliamentary Papers

c~ courtesy of

CCL Commissioner of Crown Lands

ch chapter

CSC Colonial Secretary Correspondence

D Diary

Des Despatch(es)

FB (Surveyors') Field Book(s)

HRA Historical Records of Australia

HRNSW Historical Records of NSW

J Journal(s)

L Letter(s)

LC Legislative Council

Mfm Microfilm

MS, ms manuscript

N Narrative

n note(s)

np no page numbers

P Paper(s)

PP Parliamentary Paper(s)

R Report(s)

ref reference

Rem Reminiscence, Recollection

RSC Report of Select Committee

SMH Sydney Morning Herald

VDL Van Diemen's Land

vol volume

DEFINITIONS

1788

The century or so of first contact between Aborigines and Europeans after white settlement began at Sydney Cove. In that century the contact frontier moved on and out until almost all Australia was known to the newcomers. The great world later found people it did not know of, but they knew of it, and in various ways awaited or avoided its coming. ‘1788’ includes these contacts.

‘1788’ is also shorthand for the beliefs and actions of Aboriginal people at the time of first contact. Thus “1788 fire” refers to the deliberate use of fire as a land management tool, while “since 1788” indicates a subsequent change to 1788 practice.

English stumbles to find apt words for 1788. Hundreds of pages try to define Aboriginal social units (tribe, horde, clan, mob, language group, family, kin) without achieving clarity or consensus. This book too uses words capable of imprecision:

animals

Usually includes birds, reptiles and insects.

association

Plant communities deliberately connected; a plant mosaic lacking enough evidence to identify as a template.

barren

1) treeless, or 2) useless to settlers.

bushfire

A fire accidentally or naturally lit. Some prefer the US word ‘wildfire’, but this implies that these fires are difficult or impossible to control, and that what they burn is wilderness. For Australia, and I believe elsewhere, both assu

mptions are wrong for 1788, and constricting, even defeatist, for today.

estate

Australia including Tasmania. Although comprising many ways of maintaining land, and managers mostly unknown to each other, this vast area was governed by a single religious philosophy, called in English the Dreaming. The Dreaming and its practices made the continent a single estate. In today’s terms, it blended a continuum of like-minded managers, mixed farms, and national parks.

people

Aborigines. Europeans are called ‘newcomers’ or an equivalent. It seems unjust to deprive Aborigines of the most common term for humanity simply because Europeans turned up, especially at a time when they were the only Australians. Similarly I use tribal names very cautiously, especially in the south. As Mike Powell’s article shows (see bibliography), these are mostly European inventions, not always sensibly related to 1788 life or land management. Where tribal names are entrenched I do use them; otherwise I use a more general term, such as ‘Tasmanians’. For a full list see under ‘Aboriginal groups’ in the index.

pick

Soft, green, short grass, high in nitrogen, preferred by all grass grazers.

predictable

Capable of being anticipated; certain assuming no adverse influence.

template

Plant communities deliberately associated, distributed, sometimes linked to natural features, and maintained for decades or centuries to prepare country for day-to-day working. Examples are a grassy clearing or plain beside water and ringed by open forest, an alternating grass–forest circuit or sequence designed to rotate where grazing animals fed, and a big open plain with little or no tree cover to deter animals but promote plants. To work well, templates for animals had to be kept suitably apart, but linked into a network ultimately universal (ch 8).

universal

The extent of the Dreaming; the limits of the imagined world; Australia including Tasmania; the Australian estate.

FOREWORD

Henry Reynolds

At the time of Federation there was an upsurge of interest in the Aborigines. Scientists like Baldwin Spencer and enthusiastic amateur ethnographers like FJ Gillen, RH Mathews and AW Howitt carried out research in remote parts of Australia and examined relevant written records which had been accumulating over the previous century. There was a sense of urgency about their work. Ascendant evolutionary theory suggested that the Aborigines were destined to be driven to imminent extinction by the iron laws of evolution. The widely observed decline of the indigenous population appeared to confirm evolution’s death sentence. The anthropological information sought by the scholars was endangered. It would soon disappear with the old tribesmen and women and be lost forever. And it was irreplaceable because it was assumed to embody evidence about the pre-historic origins of humankind, about language, religion, art, marriage and other social institutions. This gave these Australian studies international importance. Scientific journals in Europe and North America clamoured to publish their findings, and books on the Aborigines found readers among the intellectual elites, who used the raw ethnological data to weave sophisticated theories about human nature. But the scholars of this time had no interest in the actual Aboriginal communities living among the colonists in fringe camps or on sheep and cattle stations. They were seen as people who had lost both their racial purity and their pristine culture. They were also inclined to be irreverent and un-cooperative.

The Biggest Estate on Earth

The Biggest Estate on Earth